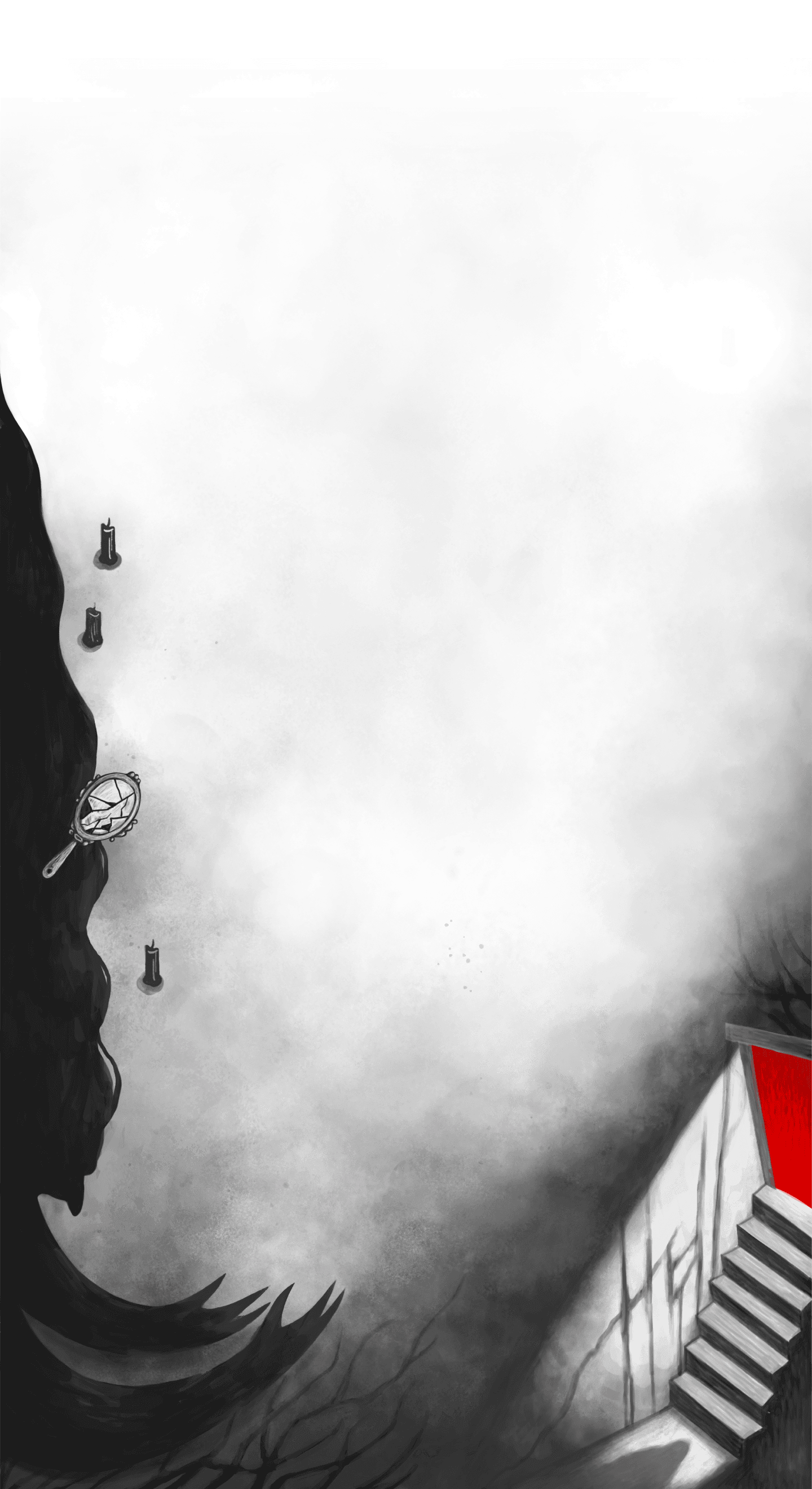

When aging women become monsters:

The Horror Trope We Can’t Escape

Aging women are increasingly portrayed as monsters across the horror genre, both local and global. The trope isn’t just frightening: It reflects deep-rooted sociocultural fears of women whose power no longer depends on beauty, youth or submission.

by

Yohana Belinda

I grew up with monsters. Not the kind under the bed, but the ones from stories my grandmother told, thick with the scent of minyak telon (eucalyptus oil) and laden with warnings.

Among them, Wewe Gombel terrified me the most.

With wild hair and sagging breasts, she is a malevolent spirit said to prey upon lost children. But she isn’t purely evil. In some stories, she protects children by preventing them from staying out too late. In others, she is portrayed as a decidedly unusual maternal guardian of abused and abandoned children.

She is both menacing and motherly, a contradiction I couldn’t define then but now find impossible to ignore.

As I grew older, my curiosity only deepened. I devoured tales of sundel bolong, a female ghost with a hole in her back, and kuntilanak, a spirit often portrayed as a betrayed woman seeking revenge, but is originally the ghost of a woman who dies while pregnant, in childbirth or due to miscarriage.

My fascination peaked one summer when Sundel Bolong (1981), starring actress Suzzanna, aired on television. I was riveted. She wasn’t just scary, she was beautiful, seductive and wronged. Her pain made her powerful, and terrifying.

It wasn’t until much later that I realized the commonness of this pattern: that women, especially older women, are transformed into monsters.

In Indonesian horror, such spirits are often born from violence, abuse or betrayal. According to a 2018 report, over 60 percent of local horror flicks featured a female ghost.

They are objectified and feared, desired and destroyed. And increasingly, they are older.

Symbols of collective fear

And it’s not just local folklore. Globally, horror has long turned aging women into symbols of decay, danger or madness.

Think of Hereditary (2018), The Substance (2024), Bring Her Back (2025) and the recent Weapons (2025), all of which portray older women with grotesque physical features who are framed as either dangerous or deranged.

Annissa Winda Larasati, who penned Memaksa Ibu Menjadi Hantu (Turning Mothers into Ghosts) alongside coauthor Justito Adiprasetio, suggests this isn’t accidental.

Patriarchal societies that prize youth and motherhood often frame aging women as failures for deviating from gendered norms. No longer seen as desirable or reproductive, their bodies are marked as deviant and threatening. Horror films exploit this perception, using aging bodies as visual shorthand for danger.

These portrayals reflect a deep anxiety about women who escape control under the traditional mechanisms of desirability and utility, presenting them as horrific reminders of both mortality and defiance.

“Horror amplifies these anxieties by exaggerating physical differences into the realm of the primal uncanny. This creates a recurring archetype of the hag or witch, whose altered appearance signals moral corruption or supernatural danger,” says Annissa.

“In Indonesia, this trope persists specifically in depictions of nenek sihir [old witch] or dukun [shaman],” she continues.

“Such representations reduce complex women to mere symbols of society’s deepest fears, aging, illness and death, denying them any true narrative agency or complexity.”

Female specters and politics

In a 2018 op-ed, Bunga Dessri Nur Ghaliyah argued that the rise of female ghosts in horror movies during the New Order era wasn’t merely aesthetic, but ideological.

Outings like 1981’s Sundel Bolong and Beranak Dalam Kubur (Birth in the Grave, 1972) often depicted women as victims of sexual violence, silenced by death, then transformed into supernatural threats. These portrayals didn’t empower women; they neutralized them.

Their rage was only allowed to exist within the limits of fantasy. In real life, such women had no voice.

The New Order’s view on gender roles was clear: Men were public leaders, strong and rational, while women were expected to be passive, patient, modest and confined to the home.

Women became monsters when they overstepped these expectations, a warning against defying the traditional roles of wife and mother.

It’s a dynamic that continues to echo today. In 2024, the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) reported 33,225 femicide cases, the highest in five years.

These are not just statistics. They are the lives behind the legends.

When a woman’s suffering is never acknowledged, maybe the only place her rage can live is on-screen, embodied as a ghost.

Unpacking the trope

The fear surrounding older women goes beyond plot devices.

In the face of immense pressure on women to achieve perfection and defy aging, they’re cultural anxieties made visible. Wrinkles are warnings; a menopausal body is repulsive.

“Horror weaponizes this fear, turning repressed anxieties about decline and death into literal monsters,” Annissa says.

“This dread even permeates daily life, evident in skincare ads that aggressively sell youth, framing aging not as natural but as a shameful condition to be fought.”

It’s no surprise, then, that the horror genre shares strange parallels with the beauty industry: Both thrive on aging as a threat. In beauty ads, aging must be resisted; in horror, it must be feared.

Sociologist Brian Brutlag argues that societies are taught to associate defilement and disgust with certain ideas such as aging, disability and bodily difference, which then manifest as fear or revulsion. Horror movies use these learned emotional responses to their advantage, turning older or disabled bodies into symbols of corruption and terror.

The woman who ages, who changes, who refuses to disappear quietly, becomes terrifying. The hag, the witch and the dukun, then, aren’t just characters. They’re cautionary tales about what happens when women stop conforming.

Shifting shadows

But not all is grim. Some creators are beginning to reshape the narrative.

Annissa points to the TV series Misteri Gunung Merapi (Mount Merapi Mystery, 1998).

“While more action-fantasy than horror, it portrays female spirits with nuance and respect. They’re powerful, yes, but also wise and layered. That’s still rare in horror,” she notes.

Filmmakers Linda and Charles Gozali, cofounders of Magma Entertainment and the creative force behind Qodrat, the 2022 box office hit that inspired a wave of Islamic horror in Indonesian cinema, say movies mirror the evolving social and political anxieties of each era.

“When these female figures emerged, it's unclear if they were purely symbolic, a form of resistance or simply a cry of the heart,” Linda says.

But today’s stories can begin to shift amid the rise of women's empowerment movements and increased female participation in the movie industry.

“If you ask me how to curb [the trope], or even if we should, I believe we must let the era decide for itself. The cultural conversation, driven by more diverse voices, will naturally shape the stories we tell," she says.

Charles agrees.

“Even within horror, there’s room for strength,” he says, referencing A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and The Terminator (1984) as early examples of the “final girl” trope, where a lone female protagonist survives.

In the sequel Qodrat 2 (2025), the ghost is male, but the most powerful scene focuses on Acha Septriasa’s female protagonist defeating evil not through exorcism, but salat.

“Her strength is rooted in faith, not ritual, allowing her to triumph,” Charles says.

“Her character also demonstrates profound love and care for her husband. She is determined to prevent him from falling under the oppression of evil forces that use her as a shield or a sacrifice," he adds.

Qodrat 2 thus challenges the moral hierarchy of the New Order era, when male religious figures like ustaz (Islamic teachers) and ulama (Islamic scholars) were depicted as the ultimate force against supernatural evil, often female in form.

Hard habit to break

So why do we keep returning to these female ghosts? Why do horror movies still cling to the trope of aging woman as monster?

Maybe it’s because these fictional figures force us to look at the things we’ve denied, at the women we’ve silenced.

She is grief, wrapped in unruly hair and bloody gore. She is justice, denied in life and demanded in death. She is what happens when society keeps telling women to be quiet, to be gentle, to disappear, and they refuse.

And maybe that’s the scariest part.

Because the power of these creatures isn’t in what they do, but in what they remind us of: the power that women have, even when the world calls us monstrous.

- Jet Damazo

- Ninda Daianti

- Renaldi Adrian

- Dian Aldiansyah

- Mustopa