Sharpness and clarity are arguably two of the most crucial elements of photography. The aim of an image is to capture the subject’s intent and then convey its message with certainty to the viewer.

Thus, it stands to reason that the substance of blurred and unfocused images would be as abstracted as its details. With technology encroaching through autofocus and AI-enhanced image processing, you’d also have to make an effort to blur these pictures purposefully.

And that’s precisely what photographer Indra Leonardi set out to do with his latest exhibition “365 by Indra Leonardi”.

The exhibition, running until Nov. 3 at Spac8 Ashta, Central Jakarta, celebrates Indra’s 60th birthday through a series of photographs taken every day from August 2023.

As the name implies, 365 is a year-long project showcasing images seen from behind Indra’s Sony camera, ranging from still life to panoramic travel pictures.

Blurred images, but never the intent

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

Unlike your Instagram acquaintance’s #OctoberDump, however, every image is in black and white and blurred on purpose.

A deliberate artistic choice? Definitely.

An embrace of the vague and indistinct as a metaphor for memory and reflection? Indubitably.

Indra, as affable as he is contemplative, says the pictures we take reflect the life we live every day. Beauty, he continues, can be found in these faults and imperfections.

He recalled a time as a student at the Brooks Institute of Photography when he captured the Olympic torch relay of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. During the creation of his book Vice Versa last year, Indra stumbled upon the decades-old pictures.

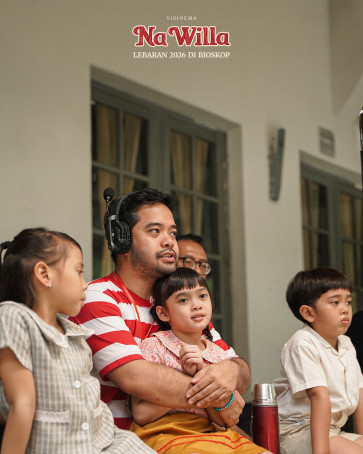

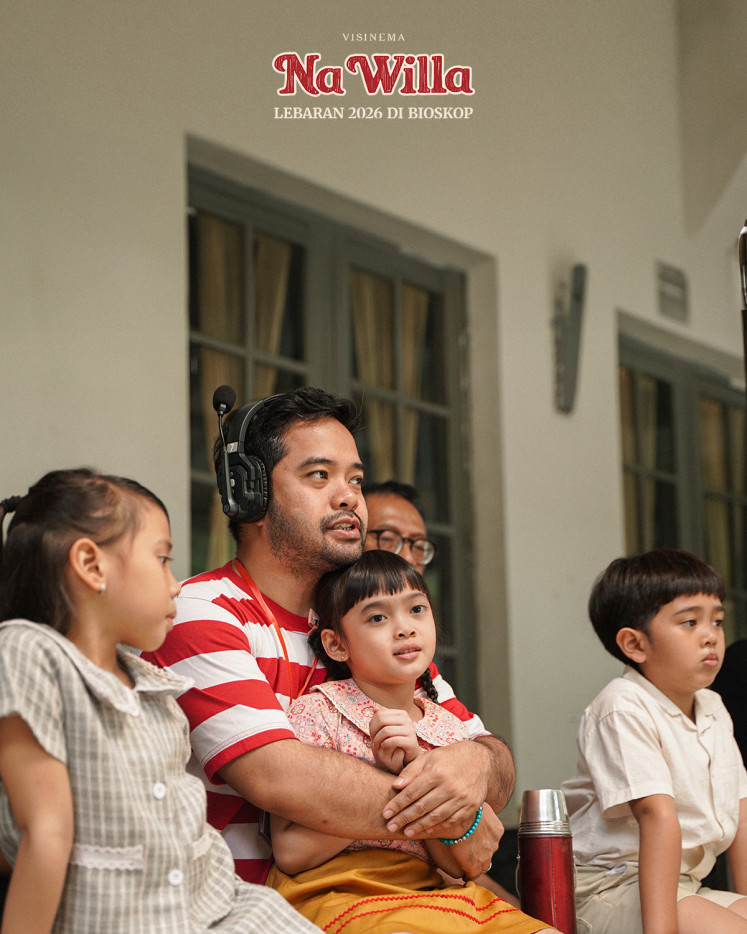

Persistence: Photographer Indra Leonardi chose to celebrate his 60th birthday with the exhibition, capturing some 15,000 pictures in the span of a year(Courtesy of Indra Leonardi)

“The photos were blurry, but somehow they were pleasing at the same time. Back then, all the photos were considered in error as they weren’t sharp and well-defined, but I found them very beautiful. I then used everything I learned back then to capture the photos [in this exhibition],” he said.

Unlike the laurels of the Olympics though, “365” focuses–or rather defocuses–on another form of splendor: That of ordinary moments savored as mementos of a well-lived life.

There are snapshots of Indra’s travels to Mt. Tangkuban Perahu in West Java, stays at the 5-star hotel The Singapore EDITION, Monday morning jaunts to the tennis court near his house in Kemang, Jakarta, and even objects around the house like lamps and charging cables.

By his estimates, he took some 15,000 photos within the year, representing what he saw with his own eyes, a sense of wonder in the mundane.

Transcendent mundanity: A softer, unfocused approach lends a sense of dreamlike wonder to everyday objects like flowers and charging cables. (TJP/Josa Lukman)

Still, there are certain subjects Indra returns to time and again, like lighting and trees, though captured with his own formula.

“If we capture the trees with a normal shutter speed from a moving car, it’s a bit whatever. But once we slow down the shutter speed, it becomes amazing. Within the year, there are pictures taken with the same camera setup with a slow shutter speed where I can more or less imagine the output, but I didn’t set out on the day with the intention of capturing a particular subject.”

The root of passion

But among the photographs displayed at the exhibition, the one image that holds a special place in Indra’s heart was nowhere to be found: a picture of his hand with his father’s.

“It is a very personal image because my father [Gunawan Leonardi] is 99 years old and sick, so it’s a very emotional and stirring image.”

Born in a photography enthusiast family, Indra was exposed to the craft from an early age. He had his fair share of hands-on experience at the family business King Foto, which his father founded in 1971, before branching out to his own studio, The Leonardi.

Surprisingly, though, he had other plans at first. In his youth, he liked going fast and dreamt of becoming a racing driver.

“My parents, though, asked me to continue the family business, so I enrolled in photography school. I was quite average back then [...] but found my groove by the second or third year and felt, ‘Oh, turns out I do have a knack in photography,’” he said.

“I think the process draws us in deeper, maybe because of the small achievements that, over time, pull us into the craft. Plus, if we visit museums and galleries, we are enriched further through observation. They add to our taste.”

Imperfection as beauty: The inspiration for "365" came from Indra’s student days, capturing the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. (TJP/Josa Lukman)

Mastering the principles and technical aspects of photography is a must, but it is merely the first stage, says Indra. Beyond that, the photographer must also be able to distance themselves from these technicalities.

“When you’re at the next stage, it’s as if everything comes to you automatically. In terms of technique, your pictures are already at that point, so you shoot with your feelings.”

But at the end of the day, he just wants everyone–photographer, subject and viewer–to be able to reflect.

“Many of the imperfections I’ve seen in my works were actually perfect in other ways. We should also celebrate the imperfections in our life because they can turn into a thing of beauty in their own right.”

Josa Lukman is an editor and head of the Creative Desk at The Jakarta Post. He is also a margarita enthusiast who chases panadol with Tolak Angin, a hoarder of former "it" bags and iced latte slurper.