Maria Cellina Wijaya earned her master’s in Global Health Delivery from Harvard Medical School in May 2024.

It was not how she imagined her Harvard story would end.

For generations, Harvard has stood as the pinnacle of academic excellence. Its dorms have housed royalty, world leaders and Nobel Prize winners.

But for Maria Cellina Wijaya, known as Celline, her Harvard chapter became a lesson in how quickly a dream can unravel.

On paper, her Boston life was ideal: Harvard credentials, a research-assistant role, a stable salary and a $2,500 stipend from the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP). For many young Indonesians, her path was proof that global dreams were close at hand.

Then she made a choice that stunned her 220,000 Instagram followers: she would "self‑deport."

“That's such a unique term, ‘self-deport’,” Celline says.

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

“It started in December, when it became clear Donald Trump would return to the White House.”

Within months she withdrew her PhD admission and formally left Harvard Medical School. Now she’s back home in Surabaya, where it feels safer.

This is America now

When Trump won his first term, I was also living in Boston. I remember how silence fell over classrooms the morning after Election Day. My friends and I were paralyzed with fear. And then stories emerged of minorities being harassed on their usual routes to class.

None of us imagined it could get worse. But it did, and Celline lived through that.

Weeks after Trump’s return to office in February, simply walking across campus became risky for international students and immigrants.

“By March, there was a lot of news about ICE officers,” Celline recalls, referring to the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“They were roaming campuses, asking for visas, passports, I‑20s [certificate of eligibility for international students].”

In April, Indonesian student Aditya Harsono was detained by ICE shortly after his visa was revoked without notice over a 2022 misdemeanor conviction for graffiti. Across New England, nearly 100 student visas were revoked, some in connection with pro‑Palestine activism, but some for minor infractions like traffic violations.

Students across universities faced visa terminations with little explanation or recourse. Reports describe how public places, parks, museums and sidewalks that once felt open now feel like surveillance zones.

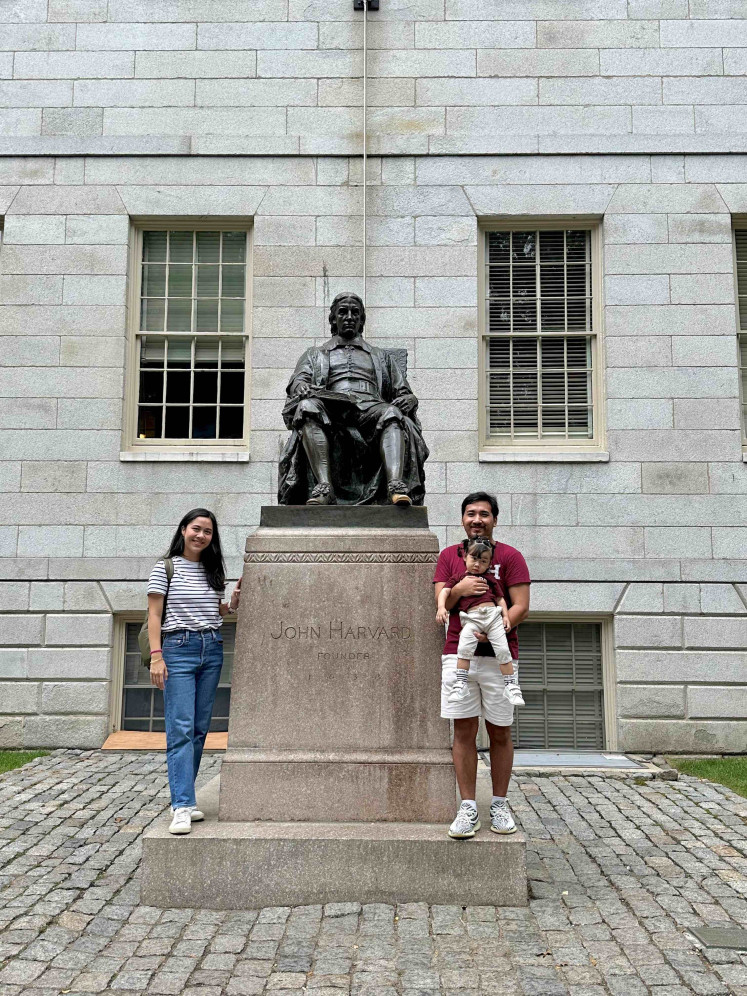

. (Courtesy of Maria Cellina Wijaya)

By May, Celline announced her decision to self-deport on Instagram, striking a nerve. What was once a nightmarish possibility became real. Her story showed what happens when the promise of the “land of the free” is revoked by the actions of an administration.

When the dream becomes a nightmare

Before boarding the flight home, Celline had secured a research role at Harvard’s School of Public Health and planned to pursue a PhD.

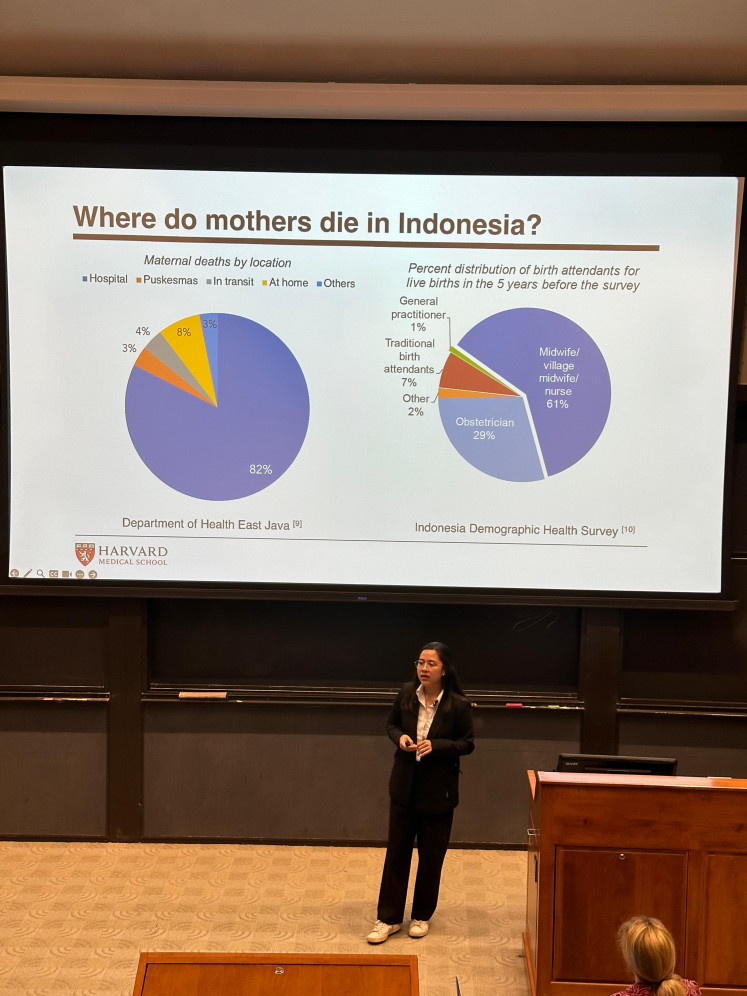

“I left Indonesia in August 2022, started my master’s at Harvard Medical School, and graduated in May 2023,” she says. “After that, I got a job as a research assistant next door to Harvard Med.”

With LPDP funding and a one‑year contract on campus, her path seemed steady, until Trump took office again in 2025.

Soon, the National Institute of Health froze new grants and slashed indirect-cost allowances to around 15 percent, down from previous levels of 27-60 percent, effectively reducing federal support for research nationwide.

The slashes led to hiring freezes, paused projects and stalled research for Harvard’s public health teams. For Celline, her friends’ stalled careers were an early warning.

Then came the personal reckoning: she was pregnant and due to give birth in June, when her contract was due for renewal.

“If my contract wasn’t extended, I would have to fly back 30 hours back to Indonesia with a newborn,” she said.

While on a J‑1 visa in Massachusetts, Celline lived with her husband and daughter, who were registered as her dependents. (Courtesy of Maria Cellina Wijaya)

Trump’s push to remove birthright citizenship by revoking the 14th Amendment only added pressure. As a J‑1 visa holder with two dependents, she had more at stake than many peers.

“Everyone told me to stay, but I had to take care of my family,” she says.

“If we get deported […] that’s just too disruptive, especially to my kid’s life. So I made the strategic choice to leave early.”

Bye‑bye Boston

The final flight from Logan International left scars.

“My daughter is only 3 years old, but she already made memories in Boston,” Celline says.

“She cried on the plane, she misses the playground and the house. She remembers.”

Back in Surabaya, Celline welcomed her second child in June and resumed her career as a lecturer in public health at University of Ciputra School of Medicine. She plans to start a residency while teaching, and maybe pursue a PhD in the UK or Australia.

Will she consider returning to the US?

“The landscape has changed. What if the damage Trump has done is already too big?” she says.

“It’s too risky. It’s just a highly stressful situation, it’s not good for your psychological wellbeing.”

Before returning to Indonesia, Celline worked as a research assistant at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard. (Courtesy of Maria Cellina Wijaya)

Celline’s journey from LPDP scholar to victim of a xenophobic policy reflects a broader shift for international students: once-promising pathways are now fraught with risk.

How much are you willing to risk for a degree that may cost more than tuition?

The US still markets itself as home of the brave. But for many brilliant scholars, it no longer feels like the land of the free.