From government talking points and corporate brand campaigns to your wannabe influencer friend’s Instagram grid, stories dominate our lives.

Speaking as a writer, and someone deeply attuned to stories rooted in both the real world and the realm of (fan)fiction, the way we buy into these narratives reveals myriad details about ourselves. In a sense, storytelling is how we relate to one another, with diction and syntax as our mechanism.

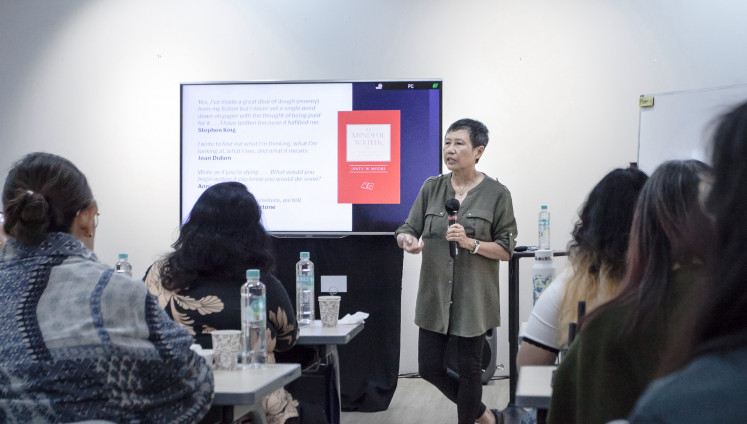

This was the crux of The Jakarta Post’s Knowledge Series: Notes from the In-Between, a one-day event on Nov. 10 centered around stories, narratives and those who shape them.

Though the day’s workshop and discussion was fully booked, I was lucky enough to catch up with the star of the show, Chinese-Indonesian-American author Xu Xi, for her insights, particularly on how stories fit into a world as fragmented as its people’s visible and invisible divisions.

When is a storyteller a writer?

Where do stories fit in a time of GPTs? Are you still a storyteller if most of your writing contributions are just prompts for the ones and zeroes to interpret?

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

“Oh, I think anybody can be a storyteller,” Xi mused.

“I mean, the question is, are we drawing the line and saying, ‘well, this is a real writer, those aren’t’, you know?”

If a book endures for centuries or even a millennium, does that make its author more “real” or legitimate? And if a writer’s work fades from memory, does that strip them of the title?

Art is a chance-y sort of thing, Xi explains. There's no predicting what will endure. To that end, she worries less about gatekeeping who gets to be called a writer, since only time will tell if anyone will still be reading what we’re writing today.

“Writing, of course, what gets written and published, contributes to literature, but not all of it will survive.”

That realization hit Xi early, during her weekly trips to the library as a child. She would gaze at the countless books on the shelves, especially in the adult section, and wonder: “I have no idea who all these people are, and yet here are all these books.”

“I think that’s why, very early on, I never thought about being a writer. I just thought, well, I know what I like to read, and I know that a lot of these books I’ll never read. You can’t read everything.”

What stories are you allowed to tell?

When is a story yours to tell? Is my story even mine, if I represent the multitudes of identities and other factors that shaped who I am in this moment?

For Xi, the story is yours if you feel it’s important and urgent enough to be told.

This becomes especially interesting in fiction, where she believes there’s no limit to what you can write.

One example she offers, particularly in the context of English-language fiction, is that, as a Chinese woman, she can naturally tell stories about Chinese people.

At this point, the question then morphs into whether she can tell a story about an American or an Indonesian. Xi has a strong case: Hong Kong birth, Indonesian parents, American citizenship. Her first novel, Chinese Walls (1994), centers on a Chinese-Indonesian family in 1960s Hong Kong.

“Well, why not? Fiction isn’t limited to who you are, but how persuasively you can tell the story. The question of whose story you can tell has a lot to do with why you want to tell it, and how you tell it.”

What you can’t do, she adds, is take someone else’s story, present it as nonfiction, and claim it as your own. That’s just lying. Fiction, however, plays by different rules. You're creating characters, not reporting facts.

“At the end of the day, even if it’s, for example, a bunch of lions who can speak, you’re still using the human experience. You’re the writer. You choose to tell this story. Why? Is it because something in it speaks to you about the human condition, something you feel is significant and important?”

What should a story actually do?

Looking back on literature classes and media literacy assignments, I couldn’t help but wonder: Should storytellers be saddled with the responsibility of inserting a message for others to discover?

Xi is wary of that. In her words, “a message feels too much like proselytizing”.

To her, the most successful works aren’t about delivering a message, but about creating a world readers can fall into, where they walk away understanding a little more about the human condition.

A story doesn’t have to point out what’s right or wrong. But it should offer a sense of how the world works, and why.

“And that, in the end, is, to me, the joys of literature.”

(JP/Farah Gumilau)

Once something is written and published, Xi believes, it no longer belongs to the author. Readers will bring their own interpretations. What’s read may be far from what was written, even if the words are the same.

“It’s like letting a child out into the world. You may have birthed this kid, but that kid’s going to do whatever it wants, you know?”

If you’re a writer, though, she thinks there’s a big difference between writing because you love the craft, and writing because you feel you have to in order to exist. In that sense, the reader’s response does matter, especially if you want to be published again.

“If you’re writing and nobody understands what you’re writing, maybe it’s great art, but maybe 50 years from now, someone will say it’s great. It really depends on how important that reader is to you. Do you write because you want to be read, or not? I happen to like to be read.”

And perhaps, as we tap the post button over and over again, we too want readers of our own.

Josa Lukman is an editor and head of the Creative Desk at The Jakarta Post. He is also a margarita enthusiast who chases Panadol with Tolak Angin, a hoarder of former "it" bags and an iced latte slurper.