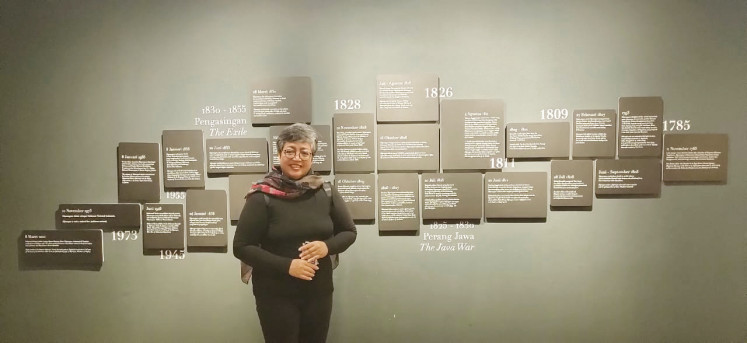

Returning to school at 47, I knew I’d be older than everyone else. What I didn’t expect was how noticeably older I’d feel, especially when some of my classmates were just 21, fresh off their undergraduate degrees (it only takes three years in the United Kingdom). The age gap didn’t just mark time; it made me a curiosity.

“But why?” they asked, when they found out I was only now pursuing a master’s degree, three years shy of the big 50.

The question came after the compliment, “You don’t look your age!” (Asians don’t raisin, remember?), but it still caught me off guard.

Why now? Because the chance finally came? Because I spent years working to support my family? Because... why not?

I mumbled something about a career switch. But the exchange lingered. Why is it so strange to see mature-age students, especially women?

That classroom moment pointed to something deeper than curiosity. It reflected a world that still expects life to follow a rigid schedule, a world still uncomfortable with women who age and refuse to fade into the background.

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

By the time I hit 40, I noticed the shift.

I was suddenly “too old” for certain jobs, hobbies or even hopes. At my age, people assume I should be applying for director-level positions. But that’s not always how it works, right?

Ageist jokes crept in—not always malicious, but always telling—implying that I’m slowing down or needing more rest than the kids at work. The punchline, of course, is always about decline. Never about growth.

Finding a scholarship wasn’t easy either. Local schemes often cap eligibility at 35 for a master’s and 40 for a PhD. International programs don’t always have official limits, but in my experience, they still lean toward younger candidates. Apparently, potential has a deadline.

It’s easy to laugh along. But like any stereotype cloaked in humor, whether sexist, racist or homophobic, it reveals how society really sees you. Or worse, how it chooses not to see you anymore.

Too old to work?

It turns out I’m not alone.

Ageism, especially toward women, is woven into everything from classrooms to clinics, CVs to casting calls. Too often, it sends the same message: Your value has an expiration date.

Men deal with it too, but aging men are often seen as wise or distinguished. Women, meanwhile, are judged by their looks, their bodies and how well they “age”.

Studies show this bias hits women harder, especially in the workplace, where youth and appearance still open doors that slowly shut after 40. And in Indonesia, the gap is painfully visible. According to the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), female labor force participation is just 53.41 percent, compared to 83.87 percent for men.

Part of this is systemic. Hiring policies still bake in age cutoffs, while cultural norms expect women to step back from work for marriage or motherhood. When they try to reenter, the job market seems to ask, “Why now?” instead of “What can you bring?”

“She asked, ‘Who’s joining?’ and when I said ‘Me’, she laughed and replied, ‘Oh, I thought it was your child’,” Vonny said. “It stung. It made me doubt myself. But something inside me just wouldn’t let it go.” - Vonny Anggraini

The late Astari (not her real name) knew that struggle firsthand. Her daughter, Renata, recalled how her mother tried to return to work in her early 40s, after years spent raising children. She even enrolled in a postgraduate program to update her skills, but every job door she knocked on stayed closed.

Eventually, she took a drastic step: She shaved nine years off her age.

She claimed to have lost all her identification documents and applied for a new ID card with a falsified birth year. It worked. She presented herself as a woman in her early 30s rejoining the workforce after a parenting break. A company hired her at a junior level, none the wiser.

From there, Astari built a strong career, proving her capability had nothing to do with her age. But the lie would come back to haunt her, only not where you’d expect.

Years later, during a serious illness, the age on her medical records read 65. But she was actually 74.

Renata recalls that doctors held off on giving stronger painkillers, because they didn’t think she needed them yet.

“If she’d been correctly listed as over 70, the doctors would’ve been more generous with the dosage,” she said.

A decision made out of necessity, just to be seen, just to be hired, ended up costing her in a way no one could’ve predicted. It’s a story that lays bare just how costly invisibility can be.

Too old to be fit?

In Indonesia, we like to say we respect our elders. But that respect often comes with quiet expectations: Slow down, step aside, fade gently into the background. Especially for women.

. (Mia Fitri)

Mia Fitri, a 49-year-old fitness coach and mother of two, is pushing back one push-up at a time.

“I focus on mature clients because I’ve seen how women are often overlooked by the health and fitness industry,” she said.

“Women tend to prioritize others before themselves, and their well-being is often pushed aside. I want to create a safe, supportive space where older clients, especially women, can reconnect with their bodies and rediscover their strength.”

Yes, our bodies change. But Mia refuses the idea that aging means inevitable decline.

“People often say, ‘Just accept that we’re old.’ No! We don’t have to give in to that mindset,” she said.

“Our bodies remain highly adaptable, even as we grow older.”

She’s seen it firsthand: Women in their 40s, 50s, even 60s doing pull-ups, lifting weights close to their own body weight, reclaiming the power they didn’t know they still had. The transformation, she says, isn’t just physical, it’s in how they carry themselves.

“One of my clients is 62, with osteoporosis and declining bone density. For years, her only form of exercise was walking. We started strength training, and after two years, her condition improved from osteoporosis to osteopenia, or one step better on the bone health spectrum.”

Mia’s work isn’t just about fitness. It’s about redefining what strength looks like. And it challenges a deeper cultural narrative that age makes women invisible, fragile or finished.

“Yes, aging comes with some decline,” she said, “but we can choose how steep that decline is. The goal is to stay at the top longer, not to accept being bedridden or fragile as inevitable.”

Too old to be seen?

In her 2014 Golden Globes monologue, Tina Fey joked that Meryl Streep’s performance in August: Osage County proved “there are still great parts in Hollywood for Meryl Streep over 60”. It was funny because it was painfully true.

In Indonesia, the same holds. With rare exceptions like the legendary Christine Hakim, women over 40 are mostly cast as someone’s mom, grandmother or moral compass. Starting late is nearly unheard of. Unless, of course, you’re brave enough to ignore the rules.

. (Vonny Anggraini)

Vonny Anggraini was 39, in a stable human resources job, when her long-abandoned passion for acting reignited. She hadn’t been on stage since college, and when she showed up to enroll in an acting class, the registration staff laughed.

“She asked, ‘Who’s joining?’ and when I said ‘Me’, she laughed and replied, ‘Oh, I thought it was your child’,” Vonny said. “It stung. It made me doubt myself. But something inside me just wouldn’t let it go.”

Her breakthrough came in 2012 with a theater troupe, performing across Java and Bali, sometimes in malls, sometimes on proper stages, but always with heart. She didn’t quit her day job, but gradually, doors began to open: commercials, short films, TV roles. A full-fledged acting career, built from scratch in her 40s.

And yes, she’s often typecast as a mother. Leading roles are rare. But once in a while, something different comes along: A fierce wife defending her husband in Tinah Buys Cigarettes (2024), a murderous shaman in Teluh (Black Magic, 2022), a villain in the upcoming Legenda Kelam Malin Kundang (Malin Kundang’s Dark Legend, 2025).

“The truth is, the ones who have it the hardest are women in their early 30s,” she said.

“They start losing lead roles to younger actresses, but they’re not yet convincing as mothers. People my age have a wider range, because we can play 30 to elderly with the right makeup. That’s why most actors in their 30s disappear and reappear in their 50s.”

When she craves something beyond maternal roles, Vonny turns to indie filmmakers and student projects who can afford to be more experimental.

“I love working with them,” she said.

“The roles are so much more diverse, from sex workers and jockeys to butchers. It’s energizing and I gain different insights from working with younger people. It keeps me humble.”

Vonny’s story isn’t just about reinvention. It’s about refusing to fade, even when the spotlight tries to move on without you.

Too old to start again?

Not every reinvention happens on stage. Sometimes, it begins in a quiet kitchen, or by the side of a road with a small cart, a big dream and zero interest in retiring from life.

. (Nina Susilowati)

Nina Susilowati, a former journalist, turned 58 this year. And she’s felt the shift that comes with silver hair. Not just in how people look at her, but in how they stop looking altogether.

“I’ve gotten lazy about dyeing it,” she said of her hair.

“And it turns out, people perceive me as even older. Agencies stopped reaching out. For live broadcasts, they want younger people. There are still jobs, but they don’t involve interaction anymore. Creative work is rarely given to older people, even when you’re tech-savvy like I am.”

As a single mother of three, Nina has always found a way. In 2015, she started selling keto-friendly foods online. Her already thriving Facebook community, Langsung Enak (Instantly Delicious), gave her a customer base. With 1.2 million members today, it helped fund her kids’ college tuition.

But even that had a shelf life. Demand slowed. Then came COVID-19, and Nina landed in the hospital for 22 days during the chaotic early waves of the pandemic.

She recovered and launched a new business, Ninago Resto, selling traditional Javanese baceman dishes. Then came another blow in 2022: A mild stroke.

By then, her children had graduated and could support her. But Nina refused to sit back and become someone to be taken care of.

In 2024, she opened a roadside gudeg (Javanese stew) stall in South Jakarta. The business grew and now she’s considering adding a second cart in another part of the city.

“People ask, ‘Are you okay with selling food like this? Are you being forced?’” she said.

“I tell them, if I were being forced, I wouldn’t do it. I enjoy meeting people. I enjoy chatting. It’s fulfilling. Staying active matters.”

Nina’s story isn’t about grit in the face of adversity, it’s about insisting on continuing to be part of the world, regardless of age, on her own terms.

The stories of Astari, Mia, Vonny and Nina resonate deeply because I’m living one too.

After I finished my master’s degree earlier this year, I had to wade through the quiet, persistent barriers of midlife job hunting. Every “you’re overqualified”, every “we can’t afford you”, every polite brush-off feels like a subtitled message: You’ve aged out.

But I haven’t. I’m still here.

We don’t talk enough about the slow disappearance women face as they age, not just from job ads or casting calls, but from conversations, expectations, even futures.

And maybe that’s why I went back to school in the first place. To claim space in a world that keeps narrowing the window of what’s considered “on time”.

So if the doors keep shutting, I’ll keep punching holes in the wall until something gives.

Because what if we stopped asking why women are still trying and started asking what we’re losing when they’re not?

Hera Diani is a journalist, communications professional and the cofounder of Magdalene.co. When she’s not wrangling words, she’s decoding life with her morbidly witty son and plotting their next adventures across Indonesia and beyond.