Every awards season, there’s plenty of buzz around the Academy Awards, including predictions, frontrunners and unexpected wins. But beyond the glitz, there are valuable takeaways, especially for Indonesia’s film industry.

One of the biggest lessons from this year’s Oscars? The power of international co-productions.

The case for international collaboration

Almost every year since 1987, Indonesia has submitted films to the Academy Awards, hoping to land a nomination in the Best International Feature Film category.

Last year’s submission, Women from Rote Island, won four Citra Awards and gained recognition at film festivals, yet it failed to make the Oscars shortlist. Meanwhile, neighboring Thailand made history by getting How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies shortlisted, though it didn’t secure a nomination.

A key trend among this year’s Best International Feature contenders was cross-border collaboration.

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

France submitted Emilia Perez, a Spanish-language film directed by French auteur Jacques Audiard. Featuring a mix of Spanish and American actors, the film exemplifies the increasingly global nature of modern cinema.

Cross-border collaboration: Film stars (left to right) Karla Sofia Gascon, Zoe Saldana, Jacques Audiard, Selena Gomez and Edgar Ramirez pose for photos at the premiere of Emilia Perez on Oct. 21, 2024, at the Egyptian Theatre in Los Angeles, California, the United States. (Shutterstock)

Similarly, Germany’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig was helmed by an Iranian filmmaker and set in Iran. And last year’s winner, The Zone of Interest, was a German-language film submitted by the United Kingdom.

These films highlight an important reality: Cinema transcends national borders.

Many of today’s most successful international films are co-productions, bringing together talents and resources from multiple countries.

This approach increases a film’s chances of securing wider distribution, particularly in North America, where Oscars campaigns demand significant financial backing. Indonesia’s official Oscar entries have, in fact, faced budget constraints that limit their ability to run strong campaigns.

With Indonesian producers like Yulia Evina Bhara and Mandy Marahimin already stepping into the co-production space, working on films outside of Indonesia, perhaps it’s time for the Indonesian Oscar Selection Committee (IOSC) to embrace this strategy, submitting international collaborations that have already garnered global attention, rather than strictly homegrown productions.

Global stories, local resonance

The Academy’s expanded membership has also led to more international films earning nominations across various categories.

This year, two non-English-language films were nominated for Best Picture, while others secured nods in Best Animated Feature, Documentary Feature and Short Film categories.

Among them, I’m Still Here, Brazil’s Best International Feature winner, struck a chord with Indonesian audiences. The film follows a woman seeking official recognition of her husband’s disappearance under a dictatorship; a narrative that draws strong parallels to Indonesia’s own history, particularly the events of 1998. Many local cinephiles took to Letterboxd, drawing connections between the film and Indonesia’s past.

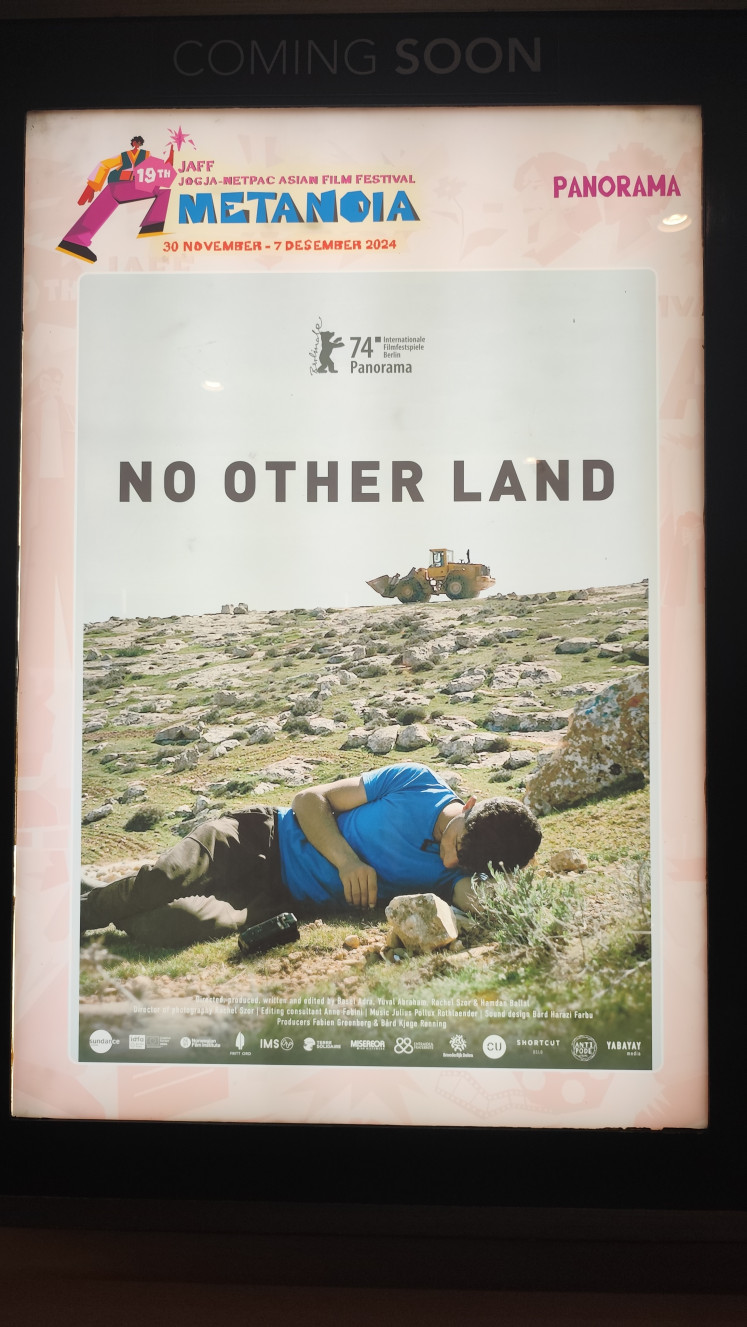

Best Documentary winner: A poster for the film No Other Land is seen on Nov. 30, 2024, during the Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival (JAFF) at XXI Theater in Yogyakarta.

(Shutterstock)

Similarly, No Other Land, which won Best Documentary Feature, explores the Israel-Palestine conflict. As the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation and a vocal supporter of Palestine, Indonesia has a deep emotional and political connection to this issue. The film premiered at the Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival (JAFF) last year, and KlikFilm has since acquired its streaming rights, making it accessible to Indonesian viewers.

Even the animated feature winner, Flow, resonated in unexpected ways.

The post-apocalyptic film follows a cat navigating a world without humans, and for Jakartans, the scenes of flooding in the film felt eerily familiar; almost like a glimpse into a climate crisis-driven future of their own city.

The ongoing challenge of film distribution

Of course, not every Oscar-nominated film makes its way to Indonesian theaters. Out of the 10 Best Picture nominees this year, three, including Anora, The Brutalist and Nickel Boys, never received a local theatrical release.

Mainstream blockbusters like Dune: Part Two and Wicked were widely available, but many critically acclaimed contenders relied on alternative avenues. Films such as Emilia Perez and The Substance premiered at Jakarta World Cinema before hitting theaters, while I’m Still Here received a limited release only after its Oscar nomination.

Conclave and A Complete Unknown were also only released in late February, just days before the Oscars. Though late, their nominations ensured they reached Indonesian theaters.

Censorship also remains a major hurdle.

Anora, for example, would likely never pass Indonesia’s strict regulations due to its explicit content. And even when a film does secure a theatrical release, it faces an uphill battle in a market dominated by two major cinema chains, where audience preferences lean heavily toward horror films and relationship dramas.

This is where alternative screenings and digital platforms come into play.

Film programmers can obtain screening licenses for limited runs, while major OTT platforms can acquire national distribution rights, just as Falcon did with KlikFilm, bringing festival favorites to local audiences.

The 2025 Oscars reinforced what many in the industry already know: To gain global recognition, Indonesian cinema must embrace international collaboration, tell stories that resonate beyond borders and find creative ways to navigate distribution challenges.

Reza Mardian is a winner of the Best Film Critic award at the Festival Film Indonesia 2024 and a "pawrent" to two rescued cats. He writes screenplays every time he finishes rewatching La La Land or Lady Bird.