"I was the heir owner of a gold store back in Lampung, and I witnessed how my own family business vanished in a matter of time," says Hadi Cahyadi.

In a country where thousands of large family-run businesses provide livelihoods to millions, his story is far too common. Research shows only 12 percent of these businesses survive into the third generation, with many failing to endure at all.

But there are lessons to be learned from those that do survive.

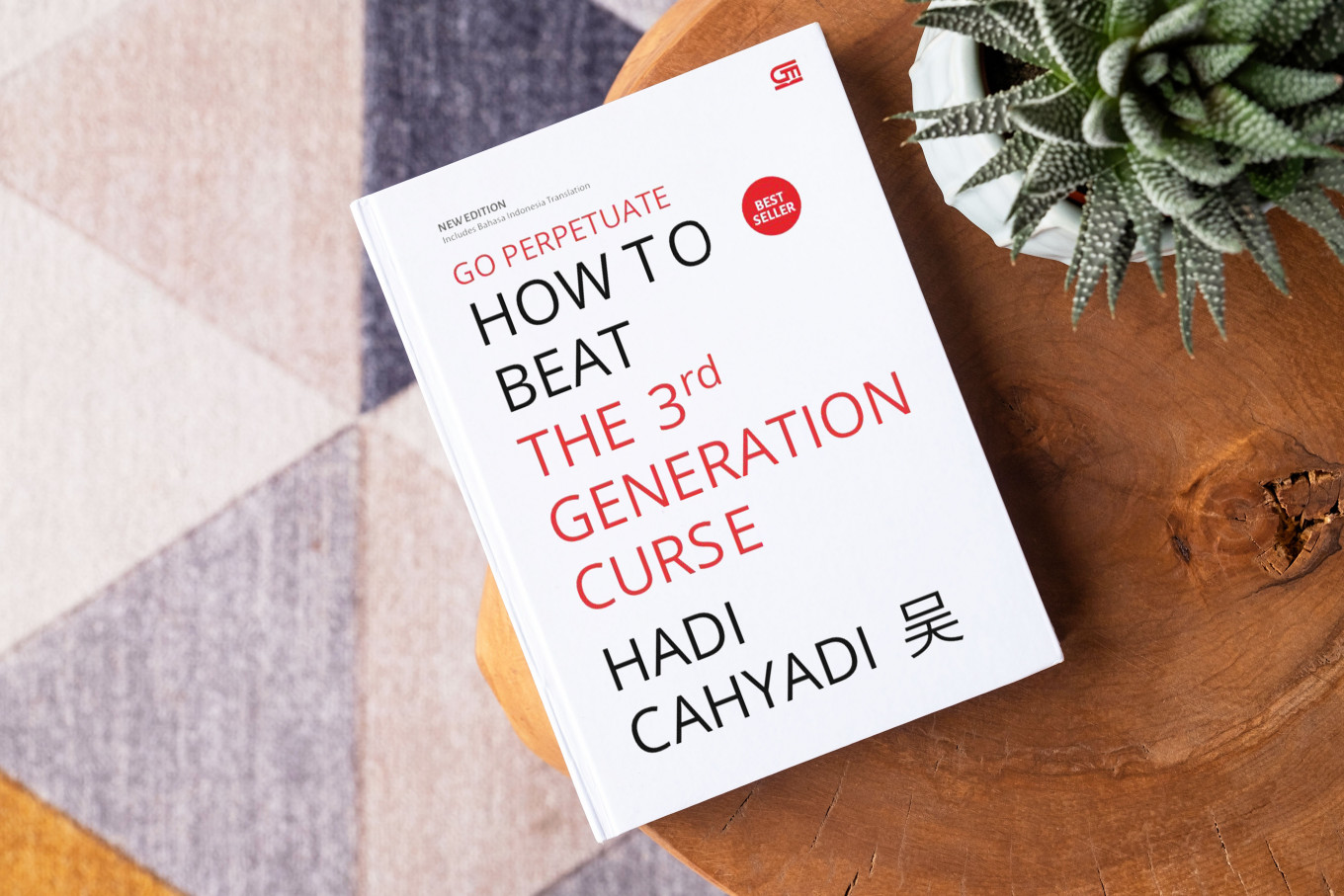

In his book Go Perpetuate: How to Beat the 3rd Generation Curse, Hadi highlights key factors contributing to the failure of family businesses beyond the second generation.

First, there are internal issues, primarily a lack of succession planning, with the next generation often unprepared to take over. Family conflicts, often sparked by blurred lines between personal and professional matters, can further destabilize the business. These disagreements, fueled by a lack of professionalism, complicate the transition.

Then there are external challenges. Family businesses must constantly adapt to shifting market dynamics. Over the past 30 years, these changes have been profound, demanding ongoing innovation and flexibility to survive and grow.

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

Hadi says he eventually cracked the code, realizing that if a family business is to survive long-term, parenting that shapes character is key to ensuring success across generations.

Familial ties

The threat internal family issues pose to a business’s survival is something both Samudera Shipping Line’s Trisnadi Mulia and Deltomed’s Jesslyn Angelia Rahardjo are all too familiar with.

"In a family-run company, one of the challenges is convincing the older generation to embrace new ideas,” says Trisnadi, now the managing director of Samudera Shipping Line.

The company was founded by his grandfather, Soedarpo Sastrosatomo, a prominent shipping magnate.

For Trisnadi, one of the biggest hurdles for the younger generation is proving their ability to lead, often made harder by the continued involvement of the second generation, whose tendency to micromanage can slow down the transition.

“However, along the way, some of the seniors have guided me, allowing me to actively engage in the business,” he adds.

Trisnadi Mulia (left), the managing director of Samudera Shipping Line, majored in architecture but his passion for business and economics led him to eventually join the family business. (Courtesy of Trisnadi Mulia)

Jesslyn, who has been involved in her family business for nearly a decade, has had similar experiences navigating relationships with relatives at work.

"At times, I have to serve as the bridge between my family members and the professionals working for our family business," says the heir to Deltomed, known for its herbal medicine products, including its flagship brand, Antangin.

No pressure

For both Trisnadi and Jesslyn, it’s important that parents don’t force the next generation to join the family business.

Trisnadi originally studied architecture in Melbourne, but says he’s always had a strong interest in "everything related to business and economics", a passion that eventually drew him back to the family business.

What’s important, he says, is to instill core principles in future generations, an idea that strongly aligns with Hadi’s message.

"What deepened my understanding of the company was being exposed to its many aspects from a young age, especially through company events," he explains.

Now a father of three, Trisnadi is teaching his children the core values of the business, preparing them at home for possible future roles.

"But there’s no pressure for them to join the family business," he says, emphasizing that even if his children don’t take over, understanding the company’s history and values is still important.

"They have a lot to learn, especially having lived abroad, and it's important for them to understand how Indonesians work," he adds.

Like Trisnadi, Jesslyn, who spent a few years in journalism before joining the business, believes successors shouldn’t be pressured into taking the reins. She says allowing younger generations to explore their passions can ultimately benefit the business.

She’s now building her own brand, Herbana, helping ensure the family business continues to evolve and grow.

Surviving forever

Both Trisnadi and Jesslyn embody the qualities needed to sustain their family legacies.

Hadi’s book outlines seven essential elements for intergenerational success, including honoring family values and allowing personal exploration, both of which are reflected in their stories. They also benefit from the trust of senior family members.

But what happens when the next generation isn’t interested?

In his book, Hadi argues that if families want their companies to last "forever", they should “leave it to the professionals”.

One option is going public, according to Bernadus Setya Ananda Wijaya, CEO of Sucor Sekuritas, which offers asset management and online trading services.

An IPO can address several issues. Publicly listing a company allows shares to be distributed among family members, potentially avoiding future disputes.

"It's ideal if the founding father is still alive, as they can divide the company's ownership. If a family member no longer aligns with the company’s values, they can simply sell their shares," Bernadus explains.

Several family-run companies, including Sidomuncul and Avian, have already taken this route. While most shares are still held by family members, external oversight helps ensure accountability.

Another strategy is to sell, like Sampoerna did when it sold to Philip Morris. This allows family members to pursue new ventures while still benefiting financially.

In some cases, like BCA, families retain ownership but rely on professionals to manage the business, ensuring continued dividends without direct involvement.

Still, some industries face challenges beyond family control.

Take the garment manufacturing sector, which is increasingly uncompetitive. In these cases, Bernadus says, government support is key, such as limiting imports and creating space for domestic businesses to diversify and survive.

"It will take some more time before we can see if the third generation in Indonesia will succeed, as many second-generation members are still heavily involved in Indonesian businesses," he says.

. (Courtesy of Hadi Cahyadi)

For Hadi, this is exactly why he wrote the book. Despite the collapse of his own family business, he believes his mission is just getting started.

"The failure of my family's business isn't the end, it’s just the beginning of a greater mission: Helping others understand how to avoid a similar fate."

Yohana Belinda writes pop culture with a business-centric twist. Her ABCs stand for ambition, bag charms and capybara.