Earlier this year, I made a detour to Bekasi, West Java, after work to meet my two-month-old nephew.

As my cousin led me upstairs to the bedroom, I expected chaos. Three boys, aged 10, eight and a newborn, in one room with their parents, I imagined pre-bedtime restlessness, bedtime meltdowns and cramped space.

Instead, I found remarkable calm.

“Before bed, they’re pretty mellow,” my cousin explained.

“They play or chat with their father, catching up after a day of school and work, and then everyone sleeps together. It’s manageable.”

My cousin had turned bed-sharing into an art form, a puzzle solved with love and practicality. The children and she sleep on a queen-sized bed, her husband on a single bed nearby, though the older boys often migrate there at night. Their house was still under construction, but they made it work.

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

Watching her, I wondered: Could I handle the same someday? The thought surfaced a familiar modern dilemma: to sleep-train or to co-sleep?

The sleeping dilemma

This question reflects a wider, global divide. In many Western contexts, co-sleeping is often seen as risky. In Indonesia and many Asian cultures, it’s natural. Medical advice, however, complicates the picture.

Ernie Yanto, a pediatrician at MyKidz in BSD City, points to the “ABC” gold standard: “Babies should sleep Alone, on their Backs, in a safety-approved Crib”.

The advice clashes with the reality for many Indonesian families, where bed-sharing is shaped by tradition, convenience and limited space.

“If parents choose to bed-share, they must meticulously create a safe, nurturing sleeping environment,” Ernie says.

. (Shutterstock)

She notes that the safer co-sleeper is usually the breastfeeding mother.

“Nature equips mothers with a protective instinct,” she explains.

“They often naturally adopt a protective ‘cradle’ position while asleep, on their side, knees bent and arm above the baby's head, to create a secure zone.”

Babies, too, are wired for closeness. In their first months, they feed often and lack a stable circadian rhythm.

“Maternal hormones and proximity at night actively help establish that rhythm,” Ernie adds.

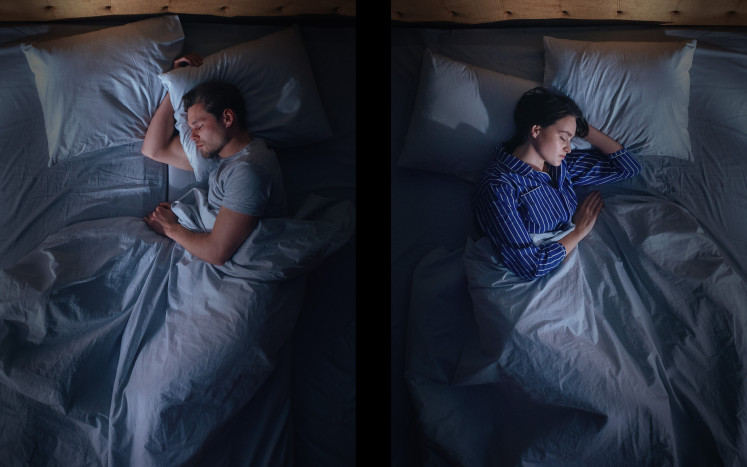

But what happens when the real challenge isn't the baby, but the other adult in the room?

The real problem

Over coffee with my middle-school friend Mitha, 29, I saw another side of the story. Not all women have a supportive partner like my cousin’s husband.

“Thasya used to sleep at 8 p.m. sharp,” Mitha told me.

“Now she fights to stay awake until 11, just to watch her dad play mobile games.”

Her voice was calm, but her frustration showed.

“She's desperate for his attention, but he says the game helps him unwind after work.”

Mitha had also endured six months of postpartum depression. Despite her parents living next door, she felt unsupported.

“I went through labor on my own. I learned motherhood from YouTube. And my husband? Always put ‘work’ as an excuse.”

She’s not alone. Studies show 60 percent of postpartum women worldwide experience poor sleep quality, while 16.5 percent develop symptoms of depression. Maternal exhaustion is less about the baby’s schedule than the absence of a supportive partner, a stronger predictor for depression than hours of sleep loss itself, a study reported.

Natasha Ghaida, a clinical psychologist at Mindfulivy, confirms that the core issue lies not in the baby’s sleep or sleep arrangements.

“It’s in the quality of parental presence and responsiveness to the child’s needs,” she says.

A united front in the bedroom

Co-sleeping and nighttime newborn care inevitably limit private time and connection for new parents. But that doesn’t justify emotional absence or disengagement.

“The key is to maintain the relationship as a couple, too, not just as parents,” Natasha emphasizes.

Small gestures, conversations, gratitude, a simple hug, can refill the “love tank”, reminding both partners that their identities extend beyond parenthood. It sustains intimacy and bonds, strengthening the family foundation.

If a father feels sidelined during co-sleeping, Natasha reframes that not as a flaw of the arrangement, but rather “a lack of preparedness for parenthood”.

It’s why communication before the baby arrives is crucial: couples need to discuss roles, limits and needs upfront. Without it, resentment and imbalance can arise. Even after the baby arrives, constant conversations about what’s working and what’s not are still necessary, especially to ensure both parents are content with the arrangement.

Practical division helps. While a mother may handle nighttime feedings, a father can support by tidying up, preparing breakfast or taking over morning duties. Such efforts shift the household from separation to solidarity; it becomes a shared responsibility.

As Natasha puts it: “Openness about what each partner can and cannot handle allows for a realistic plan that protects both the child's well-being and the parents' mental health.”

My cousin’s husband recognizes his limitations in newborn care. His support was still steady and useful: late-night massages, warm cups of tea and prepared snacks. What’s more important is his constant readiness to step in.

Paternal support doesn’t mean mirroring the mother’s role. It means playing your own part well, loving and supporting your partner as she navigates motherhood.

The transition from partners to parents doesn’t erase intimacy. It challenges couples to rebuild it consciously, within the new roles of the current family structure.

The answer isn’t avoiding co-sleeping, or chasing the perfect “sleep solution”. The real work lies in facing the nights as a team: honest, compassionate, creative and the willingness to grow together.

Allestisan Citra Derosa is a writer who often turns personal challenges into stories. She finds comfort working at local pet shops and has a knack for making any space feel like home.