There is a noticeable difference between the visitors that come to Bali now compared with those from decades ago: They dress better. The women wear straw hats and backless dresses, the men in linen T-shirts and pastel colored shorts. Everyone is dressed for fashion, not necessarily comfort, ditching the sneakers, loose cotton tees and baggy shorts popular in the 90s and early 2000s.

And it is not just a vacation thing.

At any shopping mall or coffee shop, you can find people dressed up, knowing photos will be taken and posted for their friends and followers.

“Some Gen Zs won’t even wear the same outfit twice because they know their photos will show up on Instagram,” Cempaka Asriani, founder of Jakarta-based homeware brand SARE Studio, tells me.

Social media and hypercapitalism have joined forces to keep us hyperconscious about how we look and present ourselves, pushing us into unhealthy patterns of impulse buying.

It matters little that we are being hounded by economic woes; we still shell out for affordable luxuries and entertainment, trading precious savings for lattes and lipstick, or for that seventh reusable tumbler or 12th pair of sneakers that influencers swear is what everyone is wearing this season.

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

There is even a term for it: the lipstick effect.

“You might not buy a Rolex or Apple Watch, but even when facing an economic crisis, you might still buy those cute tees or lipstick because it gives you happiness and an illusion of control,” explains Ratih Ibrahim, founder and director of the Personal Growth Counseling and Development Center in Jakarta.

Deep down, we know we have gone too far. Mindful living advocates such as Cempaka are pushing back, promoting conscious fashion and the YONO (you only need one) mindset on social media. They are even finding support in the comment section.

But I would not be surprised if this trend does not stick and people fall back to their usual retail therapy sessions.

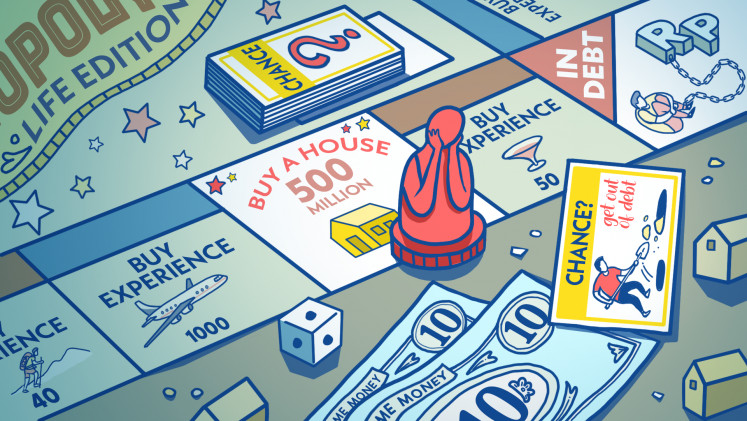

Like dieting, many of us regularly pledge to be more financially responsible, and then proceed to regularly break this promise. When we buy something we know we definitely do not need, a form of “girl math,” an internet meme that rationalizes indulgent and irresponsible spending, is probably operating at the back of our minds. In many cases, those purchases end up being a source of regret, gathering dust in the back of the closet, to be forgotten after only a few uses.

The truth is: We are not entirely to blame.

Image, image, image

Why is it so hard to resist splurging on the latest limited edition release from a brand you follow? Or the trendy new eyewear celebrities are all wearing?

The answer is social benchmarking, says Ratih.

"It is within our nature to want to be seen, to be socially accepted. And in order to achieve this, we closely monitor our surroundings,” she says.

I certainly feel this too. I feel like my wardrobe needs to change whenever I visit Jakarta from Bali, even if I am just heading to a fancy coffee shop.

Cempaka agrees: “In Yogyakarta, where I’m from, nobody judges what you wear or what you look like. In Jakarta, it’s very fast-paced. You’re always made to feel like you’re not enough.”

If this sounds like a superficial attempt to feel socially accepted, you may be right, but it is also deeply human.

“We adapt to the social context because it’s how we survive. Otherwise, we disappear into the crowd,” she explains.

What makes it more complicated now is that in the age of social media, our “crowd” has expanded.

“Back then, I only compared myself with my classmates. Now, you can compare yourself with the whole world, even Meghan Markle!” says Ratih.

This constant benchmarking can lead to anxiety, with some even sacrificing sleep just to color-coordinate office outfits the next day.

And if you fail to meet the social code? That makes you the “weird” one.

“Sure, you can try to be different and stand out from the crowd. But it’s hard to be an anomaly,” said Ratih.

And that is the kind of insecurity that fuels consumerism.

Manufacturing desire

As irrational as our desire for social acceptance may seem, it is a goldmine for businesses. They tap into and fuel desires to be seen and accepted, feelings that are fleeting, elusive and not easily satisfied, and use them to drive sales.

It does not matter what the product is. It does not even matter whether there is a demand for it.

“Businesses will create the demand. It will condition you to desire a certain product. Even if you don’t need a certain product, businesses would create that need,” says Ratih.

Why? It is how industries stay alive and keep growing, she says.

“Let’s say the color turquoise is trending. Everything comes in turquoise. That decision was made by some people in a room years before the trend plays out in real life,” said Ratih.

It is no wonder, then, that it has become so hard for some of us to resist that Rp 50,000 (US$2.96) lip and blush cream stick, even if one already owns 10. Our emotions and mental needs have been hijacked.

“The marketing is just as strong, if not a lot stronger, than the will to control yourself,” said Ratih.

And with the advent of social commerce, when algorithms know us better than we know ourselves, every scroll is a curated shopfront, and every ad is a temptation tailored to our insecurities.

So if you feel frustrated for failing to control your spending, it is not entirely your fault.

. (Budhi Button)

The turning point

So should we just give in? Or can we turn this cycle into a canvas for self-exploration and to channel our curiosity and creativity?

Certainly.

“There’s no way we can completely remove ourselves from these forces,” said Ratih.

The best way to know whether our shopping habits are out of control is our own emotional state.

“Maybe you feel overwhelmed with your purchases. You get upset at yourself for not knowing where your money goes. You have so many clothes but you don’t know what to wear!” says Cempaka, who spent years as a fashion journalist with a front row view of how consumerist machinery works.

“I think people need these ‘triggers’. Otherwise, it is very difficult to turn things around.”

For Cempaka, that sense of detachment from something essential formed the impetus to shop more mindfully. This became crystal clear to her when she redesigned her house, allowing her time to reflect upon all of her essential items in life.

“Humans don’t need a lot of rooms […] and we don’t need a lot of items,” she says.

“What we truly need is nature and human connection, but we are surrounded by this capitalistic industry that makes us feel alienated from what we really need.”

When she realized that her closet was too small for all her clothes, she went on a massive decluttering process and cut her wardrobe by half.

“That’s an essential process for anyone who wants to shop more mindfully. It allowed me to pause, to be more aware of my belongings and to reflect on my personal style and values,” said Cempaka.

Shopping mindfully is not about sheer willpower. There are too many external forces, too much money in the industry trying to dictate our spending, that it is almost permissible to lose control over our spending.

But recognizing the emptiness that mindless consumerism leaves behind might just be the first step toward taking back control.

“The marketing is just as strong, if not a lot stronger, than the will to control yourself." - Ratih Ibrahim

Alternative lifestyle

That said, there is no one-size-fits-all definition of what mindful shopping means.

Maybe for you, it means having a “no shopping” month every other month. Maybe it means sticking to a strict shopping budget. It is entirely up to you to decide, and it should bring you peace, not pressure.

Thankfully, big cities are becoming hubs for alternative lifestyles, complete with communities of like-minded people.

Cynthia S. Lestari, founder of Life With Less, an educational platform about mindful living, launched Bersaling Silang in 2023 in Jakarta, Bandung and Surabaya.

The idea is simple: People can exchange items, regardless of the value.

“We operate on the principle of usefulness. So if you donate shoes, but you need, say, a scarf, then go ahead and take the scarf. You’re not required to take items based on the value you give,” she says.

“We don’t want people to think of the monetary value, because I think that prevents people from being mindful.”

The organization simply makes sure that all items meet certain quality standards and that everyone who participates registers in advance to make certain that everyone contributes.

Pre-loved e-commerce platform Tinkerlust is also in the business of mindful and sustainable shopping.

“Some people form emotional attachments to their purchases. Perhaps it’s their first luxury bag. Perhaps they’re worried they can’t afford that bag anymore,” says Aliya Tjakraamidjaja, cofounder of Tinkerlust.

Whatever the meaning is, when the wardrobe is full and it is time to let some of these items go, “it can be hard for them. That’s why we educate people that selling their stuff isn’t embarrassing. We preach living minimally, to own items that only spark joy”.

We may never have a collection made entirely out of items that spark joy. Even Marie Kondo gave that up when she had a baby.

But realizing that our shopping impulses are shaped by various capitalistic forces far bigger than us? Perhaps the awareness that we are not entirely at fault is what we need to reclaim our choices and start shopping for the right reasons.

Michelle Anindya is a writer and journalist. From her home in Bali, she writes about anything from coffee to tech.