One morning about 10 years ago, I sat on my bed, struggling to come up with a coherent outfit.

I was a fledgling fashion student with an invitation to Jakarta Fashion Week, determined to turn heads (and cameras) despite a wardrobe filled with approximations of global trends courtesy of Forever 21 and H&M.

Well, at least until the 1 p.m. class that day, when our professor screened a documentary about the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, where a major structural failure in a building housing five garment factories killed more than 1,100 low-paid garment workers and injured some 2,500 more.

Between stories of survivors losing limbs and drinking their own urine just to stay alive, that “emergency” trip to Zara suddenly felt obscene.

Yet a decade later, despite a career change and a paycheck that sustains a modest vintage handbag collection, I still find myself throwing on that one Uniqlo cardigan that probably half of SCBD owns. The beige one. You know that one.

Maybe, just maybe, fast fashion has really become a state of mind. Or worse, a habit we’ve dressed up in better aesthetics, secondhand, vintage or “quiet luxury”, while still chasing the same thrill of the next new thing.

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

Fast fashion, faster trends

Fast fashion, as we know it, was coined by The New York Times in 1989, describing the Spanish retailer Zara’s weekly shipment of new stock from its headquarters in Spain to its then-only New York store. Back then, inventory rotated every three weeks, with just 15 days between idea and the final product.

Even more staggering is the rise of so-called ultra-fast fashion, led by brands like SHEIN. In 2023, the company reportedly produced 10,000 new designs daily, with average prices less than half of Zara’s.

(Shutterstock)

Coupled with falling production costs and rising consumer spending, global clothing production doubled between 2000 and 2014, while the number of clothing purchased per capita rose by approximately 60 percent, according to research by McKinsey.

Over coffee on a rainy afternoon, Ratna Dewi Paramita, the head of the fashion program at Binus University, tells me that fast fashion’s relative affordability has allowed more people to partake in a cultural expression, rather than reserving it for those who can afford high price tags.

“Aesthetically, you get the look, even if the value is very different, different materials, different craftsmanship. But you can’t see them on social media, so you can get away with the styling.”

The actual price you pay? A truckload of polyester, hit-or-miss quality, blatant duping and questionable production practices with both ethical and environmental consequences. But hey, at least you got something that allegedly looks like quiet luxury if you squint from a block away.

Yet for everything we lambaste fast fashion for, the luxury sector is not without its demons either.

Just last year, Italian authorities investigated third-party suppliers for luxury brands, with prosecutors finding that Dior paid US$57 to produce a $2,780 bag, with evidence of less-than-luxurious working conditions for its workers.

You also probably have seen the now-viral TikTok video by model and content creator Wisdom Kaye, whose US$18,000 Miu Miu haul began falling apart mid-unboxing. Even the replacement failed, this time on-camera.

Ratna frames these cases as symptoms of a marketing machine built on illusion.

Consumers, she continues, have always been scapegoated, with “consumer demand” becoming the keyword for every decision made. However, consumers are also confined to a system that is coming apart at the seams.

“Consumer demand is like fuel, overproduction is the engine and marketing is the accelerant,” she added.

“It keeps going and going, and so it’s really about addressing the system first.”

Buy now, regret later

If fast fashion is defined by speed, disposability and psychological urgency, what happens when those same traits show up in how we try to be more sustainable by shopping secondhand?

As massive as the role of the marketing department and their influencers in the saga, ultimately it’s the innate, instant rush of dopamine that comes from clicking “checkout” that drives consumption.

“It’s a bit like you’re in it for the thrill of it,” agrees my friend Aria* as we sat at Starbucks later that evening to inspect her newest purchase, a second-generation Coach Rogue from 2017 in oxblood. She trusted my judgment because, at one point, I owned six of them.

We joke about running out of space at home, a distinctly first-world problem. Meanwhile, the forum where we get our handbag information from has members who own 40, 50 or even more, including special-order Birkins and Kellys.

By comparison, my own collection of 31 seemed modest.

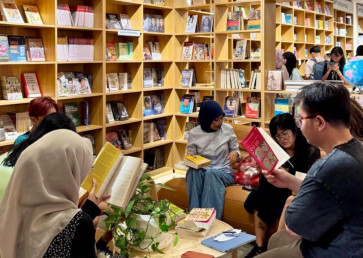

(JP/Josa Lukman)

“Speak for yourself! This is bag number nine, and my husband side-eyed me like I was a KPK suspect!”

I protest over my acai refresher; I make space by selling or giving away one for every new addition. Surely that counted?

“You bought a Phillip Lim satchel, didn’t like how it was too big and heavy, sold it below market price, regretted it, then bought another one in the exact same size that you hated. If that’s not conspicuous consumption, I don’t know what is.”

And she isn’t wrong. Even if the bag was pre-owned, I wasn’t exactly saving the planet, I was just chasing the high in a slightly more palatable package.

Though I grumble about how the medium I wanted was more expensive than the large, Aria’s jab hits the mark: between me securing the bag(s), the fast-fashion mindset has followed me nearly a decade after fashion school.

Ownership, not optics

Over the years, the thrill has morphed from buying a polyester Zara top for 40 percent off and a voucher vaguely resembling something from Milan Fashion Week to panic-buying a Loewe Amazona because it was the only one under Rp 4 million ($238).

Ratna confirms what I already suspected.

(Shutterstock)

“The bad effect of fast fashion is that we don't value the product anymore. We used to have emotional attachment with the clothing that we have, but everything feels more disposable because we want things to be on trend. We just want to buy,” she says.

“And I don’t think resale is the answer to that.”

That stopped me mid-sip. Surely my budding collection’s raison d’etre wasn’t built on a false premise? Did sustainability become justification rather than reduction?

“Sustainability as a whole is a way of life. It’s not the material and it’s not the price, but how we value something,” she emphasizes.

If resale is supposed to lengthen a product’s lifespan, it also depends on the product. Cheap fast fashion, Ratna says, will likely fall apart after two more owners just because of its poor quality.

At this point, I was ready to smugly point out that the Gucci I picked up is probably a decade old anyway, but she’s also adamant that the way we shop and the way we value the item is at the heart of the matter.

“If you buy 20 pre-owned bags, it’s still consumption, it’s still not sustainable. At the end of the day, it’s an excuse to buy more.”

“Again, you need to have a buying decision that is calculated, not impulsive,” she says.

“You need to be responsible for what you’ve bought, no matter the price or material. It’s really all about ownership.”

While being called out twice in a day was not where I thought this article was going, I suppose a wake-up call is.

Thus, with the guilt of a decade’s worth of fashion decisions heavy on the back of my mind, I resolved to go back to my closet with intention, even as the sheen of novelty slowly faded out from the bamboo handles.

Josa Lukman is an editor and head of the Creative Desk at The Jakarta Post. He is also a margarita enthusiast who chases Panadol with Tolak Angin, a hoarder of former "it" bags and an iced latte slurper.