My Sundays usually start slowly, with a rolled yoga mat or feeding stray dogs in the hidden slums of the city. But this one is different.

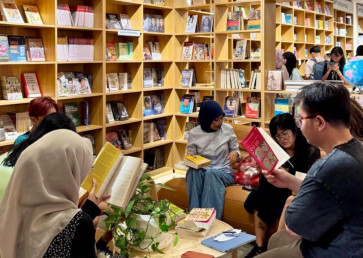

This Sunday finds me at the Lapangan Banteng park in Central Jakarta, with a glove on my right hand and a bin bag on my left, bending down to pick up a stranger’s candy wrapper or, worse, a cigarette butt.

I’m joining a cleanup with Trash Hero Jakarta, part of a global network that started in Switzerland in 2013 and now operates in 15 countries.

The routine is simple. There are 17 of us this Sunday, walking the perimeter of the field, picking up trash—mostly plastic—and sorting it as we go. There’s an unspoken rule though: Be careful not to throw away someone’s half-finished drink. They might come back for it.

The work is unexpectedly calming. Maybe it’s the morning breeze. But a quiet question hangs in the air: What does this actually accomplish?

The last line of defense

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

At its peak before the pandemic, Trash Hero had nearly 80 active chapters across Indonesia, each one adapting to its local context. In Jakarta, volunteers meet at Lapangan Banteng every Sunday at 7:30 a.m. In Canggu, Bali, they also meet every Sunday, gathering at 4:30 p.m. on Batu Bolong beach.

For volunteer Tony, 44, this weekly habit is about teaching his kids and their friends, a group of 10- to 14-year-olds.

He says the kids don’t show much interest or awareness at first.

“But after a few sessions, their understanding clicks in,” he says.

Having lived abroad, Tony wants his children to learn that public cleanliness is a shared duty, like it is in Japan or Singapore.

His point hits home. As city-dwellers, we’re surrounded by concrete. Nature is a place we drive to. Our waste disappears in trucks and landfills—an invisible system we rarely feel responsible for.

Krishna, the chapter leader, notes that in rural areas, the connection to nature is direct.

“In East Nusa Tenggara or Biak, nature is home, livelihood, identity and geography all at once.”

But he is clear: Cleanups are not the solution to the waste crisis.

“A cleanup is essentially just moving trash from point A to point B,” he says.

“It’s the last line of defense. By the time it reaches the ground, we’ve already failed.”

The real work, he says, is to address the production problem.

The upstream problem

Indonesia produces 33.6 million tonnes of waste a year. Forty percent of it is not properly managed. According to the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi), the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) industry is a major part of the problem.

This domestic crisis is made worse by over 260,000 tonnes of imported plastic waste, despite a 2 percent impurity limit meant to limit it.

The influx is driven by market demand. Local recycling businesses need high-quality scraps, and manufacturers need raw materials, consuming about 5.83 million tonnes of plastics like polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP) in 2017 alone.

The issue isn’t just about individual responsibility but a tangled system of production, policy gaps and global trade.

“This is an upstream problem,” says Krishna.

But those with the power to fix it often choose easy sustainability campaigns over real change.

He points to a past collaboration offer from a major FMCG skincare brand.

“It sounded nice at first,” he says.

“But their products use plastics that are hard to collect, return, or recycle.”

The disconnect was obvious.

“We asked them: Why is cleanup the answer? Why not redesign your packaging? Why not change how you produce?”

One of the biggest pollutants from FMCG is sachets. The average Indonesian throws away about 4 kilograms of sachet waste per year.

“If you go to Huamual, six hours from Ambon, the nearest landfill is a three-hour boat ride or a six-hour drive. But plastic from every major brand is everywhere,” says Krishna.

If nothing changes by 2030, we will have 1.1 million tonnes of sachet waste each year, creating environmental and social losses worth up to Rp 1.7 trillion (US$101.71 million) annually.

Into the policy room

While the root of the problem is upstream, the people downstream hold essential knowledge. This is why Trash Hero Jakarta doesn’t just clean; they step into policy rooms.

Once inside, they face a dual challenge: not only to reshape policy, but to first embody it.

In 2023, the Jakarta Legislative Council’s Commission A invited them to help socialize the city’s Waste Management Regulation. At the first meeting, the committee served bottled water.

“After we gently pointed it out,” Krishna recalls, “the bottles were gone. They used glassware in every meeting after.”

This small shift shows a core truth: environmental governance is about institutional behavior, not just rules.

Later, when Jakarta’s Regional Development Planning Agency (Bappeda) asked them to review the city’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) report, incineration was listed as the main waste solution.

“It may reduce the volume of waste,” Krishna cautioned, “but not the waste culture.”

He suggested an alternative: a community-based maggot composting facility in Cilincing. It was low-cost, regenerative, and scalable.

“We’re not against technology,” he says. “We’re against shortcuts.”

The agency listened. Officials traveled from city hall to Cilincing to see the project, meet the organizers and ask questions.

Whether the final report changed is unclear. But the process proved something: Knowledge from the ground, rooted in lived experience, has the power to shape policy.

My realization comes slowly. To truly stand with that grassroots power, I need to understand that my simple act of picking up a piece of plastic trash isn’t about saving the park. It’s about refusing to ignore the system that dropped it there.

After an hour of scouring the park for thoughtlessly discarded waste, we crouch down to sort out our four-kilogram haul, modest compared to other weekends.

I haven’t fixed Jakarta’s waste crisis. But I showed up.

And I’ll keep showing up on quiet Sundays, after long work weeks, maybe even on my birthday. When the commute feels too far, I’ll show up on my own street.

If we can turn necessity into ritual, then perhaps, one day, waste will stop being something we create.

Allestisan Citra Derosa is a writer who often turns personal challenges into stories. She finds comfort working at local pet shops and has a knack for making any space feel like home.