A couple of nights ago, I went down a Threads rabbit hole and found myself in the middle of a heated debate. The kind only pawrents know how to escalate.

It began with a woman sharing her desire to adopt a cat. Her husband works long hours, and while waiting for a baby, she hoped a cat might ease her loneliness. But there was a catch, it had to be purebred.

The outrage came fast. For longtime rescuers, this kind of breed obsession is a major red flag.

I understood why. After more than five years of rescuing strays, I’ve seen what happens when adoption becomes just another form of consumption. Too often, these so-called “rescues” are treated like temporary accessories or breeding stock, only to be discarded when the novelty wears off.

Adoption is about giving animals a second chance, not collecting another lifestyle marker. But even that phrase, second chance, deserves scrutiny.

It’s not enough to just adopt

Thank you!

For signing up to our newsletter.

Please check your email for your newsletter subscription.

We promote adoption as the ethical choice, the moral alternative to buying. But let’s be honest, choosing adoption doesn’t automatically make you a good pet owner.

If you think bringing home a stray is already a badge of virtue, I’m here to say: Think again.

Jakarta’s streets are overflowing with cats and dogs, many abandoned, sick or injured.

I’ve biked 2 kilometers at 10 p.m. to pick up a kitten whose body was a crust of scabies, her eyes and mouth sealed shut. I’ve carried another off a roadway, her tiny form already alive with maggots. Not only that, but I wiped the blood of a poisoned cat who shrank day by day until she looked vacuumed by death itself. I’ve taken in the one-eyed, the burned, the crushed and the chained.

The numbers speak for themselves: Jakarta alone has over 754,400 stray cats based on official 2024 data, while stray dogs remain underreported.

(Courtesy of Streetfeeding.bsd)

Shelters like Pejaten Animal Shelter, which has rescued thousands since 2009, are at capacity. Still, adoption rates remain stagnant, and abandonment continues to rise.

“Most were abandoned after divorces, breakups or relocations,” a Pejaten volunteer told me at the recent Indonesia International Pet Expo.

Some of them were once adopted animals, returned when they didn’t meet expectations.

“They claim the animal is broken or too difficult to love,” she said.

But rescued pets aren’t blank slates. They come with fear, trauma and quirks. And healing takes more than food and a bed. It takes time.

From my experience, earning the trust of a rescued animal doesn’t follow a fixed timeline. Bulan, the scabies-encrusted kitten, allowed me to touch her after a month and a half. Koi, a seemingly unharmed stray, took three years. The shift happened only this year, when she fell ill. A single vet visit transformed our coexistence into constant companionship, a bond that now feels more like sisterhood.

The deepest trust doesn’t come just from healing trauma. It comes from proving, over and over, that you’ll stay.

“Adoption isn’t about finding the perfect pet,” the volunteer added.

“It’s about becoming the kind of person who can offer a life worth living.”

Motives matter

To understand why so many adopters end up abandoning their rescues, I reached out to Indira Diandra, a creative director and the woman behind @staypurrvlub, where she blends rescue stories with sharp-witted, compassionate commentary.

Reflecting on the viral Threads post, the woman’s desire for a specific breed may have sparked online anger, but what really struck us was her reasoning: loneliness.

“We often take this world for granted and believe nature and animals exist for our benefit, in this case, a temporary comfort tool,” Indira explained.

This anthropocentric mindset, placing humans at the center of the universe, reduces animals to emotional tools, performative acts of kindness or lifestyle accessories. All in the name of giving them a “second chance”.

Indira challenges this mischaracterization.

“When paired with human-centered motives, it frames the animals as flawed and the human as savior. The opposite is closer to reality.”

The phrase “second chance” implies the animal must redeem itself by being well-behaved. And when they don’t, they get abandoned. Again.

“Obviously,” Indira adds, “the real ones needing a second chance are us.”

This resonates deeply with me.

My rescued cats gave me something I didn’t know I needed, a second chance to appreciate the life I already had. Adopting them taught me that abundance isn’t about having more. It’s about sharing what you already have. For me, it’s the way to live with joy.

What accountability actually looks like

If animals don’t need to prove their worth, then what does true adoption require of us?

At reputable shelters, the screening process is rigorous, checking for stable housing, legal residency, household members’ ages and roles.

Doni Herdaru Tona, founder of Animal Defenders Indonesia, told me the process can be complicated.

“Even if a family is ready, the neighborhood might not be,” he explained.

“If the area isn’t dog-friendly, the adoption simply won’t happen.”

Adopters must commit to vaccinations, sterilization and ongoing care. This is often where applications stall, deterred by cost or logistics.

(Courtesy of Dayu)

But Indira challenges the idea that only the privileged can adopt responsibly.

“I’ve met security guards and street vendors whose pets are not only healthy, but visibly content,” she said.

For medical care, they rely on subsidized programs.

“The most important part,” she added, “is that they never left.”

When staying matters more than starting

I thought of my own aunt, Tante Vera, who lives with chronic illness and dwindling income. After years of dialysis and caring for her husband post-amputation, she still makes sure her pets see the vet.

When her 10-year-old cat Dion had a urinary blockage, she called every clinic she could until one offered a discount, remembering her from past rescues.

“When you do things with sincerity, you don’t just get kinder,” she told me. “You get luckier.”

That same depth of accountability defines Dee Nugraha, the founder of @streetfeeding.bsd.

For nearly a decade, she funded her street-feeding work herself. Then the pandemic hit. She resigned from her job to focus full-time on rescues, her husband’s salary was cut, and her son was accepted into medical school, a proud milestone with a daunting price tag.

Amid this financial pressure, she was rescuing 150 cats from a dumpsite, while already fostering 30 in her own home.

(Courtesy of Dayu)

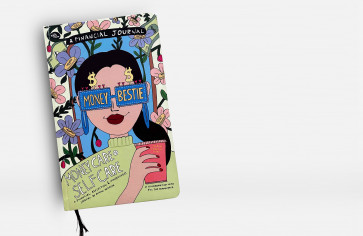

“If you want to endure, you always have to get creative,” she says.

To manage, she mobilized a network of friends and vets to perform a large-scale trap-neuter-release operation. She also sells merchandise, creating a sustainable lifeline for the animals.

Despite rescuing hundreds, Dee has formally adopted only one animal into her home: a dog she saved from slaughter.

That choice came at a cost. Her family, citing cultural and religious beliefs, no longer visits. At gatherings, her cooking goes untouched.

Her conviction, however, is unshaken.

“My life is fuller this way,” she says. “I have chosen to live by my own truth.”

Ultimately, adopting is about accountability. It means showing up, learning and staying, even when it’s inconvenient.

It is not the animal that has to prove they’re worthy of our homes. It is us who need to prove we’re worthy of their trust.

Until we can answer that honestly, maybe the kindest thing we can do is to love them from afar.

Allestisan Citra Derosa is a branding agency writer covering creative and cultural subjects, including luxury and fashion. She's pursuing journalism as a way of understanding the world and her place in it.